Friday, October 31, 2008

Assignment (Sem 200810)

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Credit crisis & climate change efforts

posted by Eugene Pek, 30 October 2008, Pandan Terrace

Visit the link below for more on Financial crisis has lessons for climate fight: expert

What is carbon finance?

posted by Eugene Pek, 30 October 2008, Pandan Terrace. Eugene acknowledges the credit of the author(s), whose name(s) are not mentioned in the source, of this Q & A article (sourced online on 20 October 2008).

Source: Gaël Grégoire, Carbon Finance Instrument to Improve Coastal Zone, Solid Waste Management, MEDITERRANEAN WORKSHOP ON INTEGRATED COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT (ICZM) POLICY, Alghero, Sardinia (Italy), May 19-21, 2008. World Bank/METAP

What is carbon finance? Carbon finance is the general term applied to resources provided to a project to purchase greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions (“carbon” for short). Commitments of carbon finance for the purchase of carbon have grown rapidly since the first carbon purchases began less than eight years ago. As of May 2004, the global market for GHG emission reductions through project-based transactions has been estimated at a cumulative 320 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent since its inception in 1996. Asia now represents half of the supply of project-based emission reductions, with Latin America second with 27 percent. Volumes are expected to continue to grow as countries that have already ratified the Kyoto Protocol work to meet their commitments, and as national and regional markets for emission reductions are put into place, notably in Canada, Japan and the European Union (the European Union has already put in place its Emissions Trading Scheme as of January 2005).

Why do greenhouse gas emission reductions have value? Meeting the Kyoto targets will require public and private investments. Many industrialized governments that have ratified the Protocol have already begun implementing domestic policies and regulations that will require emitters to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, according to the established targets. So far, experience has shown that the cost of reducing one ton of carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas) can cost from $15 up to $100 in industrialized countries. By contrast, there are many opportunities to reduce greenhouse gases in developing countries at a cost of $1 to $4 per ton of carbon dioxide. Hence, an emission reduction that was achieved at a lower cost has value to a public or private entity in an industrialized country that is required by regulation to reduce its emissions.

What is the World Bank’s involvement in Carbon Finance? The threat climate change poses to long-term development and the ability of the poor to move out from poverty is of particular concern to the World Bank. The carbon finance activities of the World Bank are a natural extension of the Bank’s mission to reduce poverty. The Bank makes every effort to ensure that poor countries can benefit from international responses to climate change including the emerging carbon market for GHG emission reductions. The private market for emission reductions, still in an early stage, does not yet have significant volume, and the potential benefits have not reached developing countries. These countries, particularly the poorest among them, are bypassed by the carbon market and the potential development benefits it would bring. The World Bank’s carbon finance products help grow the market by extending the frontiers of carbon finance to new sectors or countries that have yet to benefit, and to reduce market entry risks for other buyers.What specific role is the Bank playing in the development of a market for carbon trade? The role of the Bank through its Carbon Finance Unit has been one of market facilitator and catalyst. The Bank has made significant efforts in the development of the carbon market, first by launching the Prototype Carbon Fund (PCF) to demonstrate how to cost-effectively achieve GHG reductions while contributing to sustainable development. More recently, the Bank launched a series of carbon funds to expand learning-by-doing to other countries and economic sectors, and to address market failures, such as through the Community Development Carbon Fund (CDCF) and Bio Carbon Fund (BioCF), which are designed to enable smaller and rural poor communities to benefit from carbon finance. The Bank has developed a balanced approach between stimulating demand as a buyer in the early stages of the market and its support to sellers to tap new and additional sources of funds from carbon trade to support their sustainable development and to alleviate poverty. This will consist of meeting the demand for capacity building and technical assistance through Carbon Finance (CF) -Assist, and designing instruments in consultation with developing countries to enable them to directly access the market.

Who are the beneficiaries of the Bank’s actions in carbon finance? The main beneficiaries of the Bank’s actions in the carbon market: a) The global community. The Bank’s efforts to catalyze a market for greenhouse gas mitigation and sustainable development hopefully contributes to the success of the market mechanisms, which are essential to lowering the cost of global action on climate change. b) The Public and Private sectors that wish to participate in the market. Through the establishment of Carbon Funds, and by pooling early participants in the market, the World Bank has reduced the market entry risk for other market players. The Bank’s procedures to create carbon assets are in the public domain. c) The least developed countries and poor areas of all developing countries. The Bank is involved in market areas that the private sector simply won’t go because they perceive the risk as being too high. By doing this , the World Bank is helping to bring the benefits of carbon finance to those parts of the world that would be by-passed by the market. The Bank provides technical assistance in order to develop the set of procedures and institutional arrangements that can make the market more sustainable. For example in one developing country, it took 18 months to get the first approval for a carbon finance project. Now there are almost a dozen projects in that country.

The Bank has created several carbon funds. How do they work? Who owns these funds? The World Bank manages several funds and facilities comprised of public and private participants. These funds are public or public-private partnerships managed by the World Bank as a Trustee. They operate much like a closed-end mutual fund; they purchase greenhouse gas emission reductions from projects in the developing world or in countries with economies in transition, and pay on delivery of those emission reductions. The emission reductions can be used against obligations under the Kyoto Protocol or for other regulated or voluntary greenhouse gas emission reduction regimes. All the emission reduction credits are purchased on behalf of the public and private sector Participants in the funds. The World Bank is acting as an honest broker to ensure that the benefits of carbon finance make their way also to the developing world and to countries with economies in transition. The World Bank regularly consults with a wide range of stakeholders, including the PCF’s Host Country Committee, about the design and operation of these carbon funds.

Why do investors and governments find the World Bank Carbon Funds an attractive business proposition? Companies and governments are attracted to the various Carbon funds of the World Bank by the proven record of the World Bank in providing shareholders with Kyoto-compliant certified emission reduction assets at a guaranteed low price. Additional benefits for investors include the acquisition of high-value knowledge and intelligence on carbon finance and emerging national, regional and international markets.

Who are the main players in the carbon market at this point in time? Companies and governments are attracted to the various Carbon funds of the World Bank by the proven record of the World Bank in providing shareholders with Kyoto-compliant certified emission reduction assets at a guaranteed low price. Additional benefits for investors include the acquisition of high-value knowledge and intelligence on carbon finance and emerging national, regional and international markets.

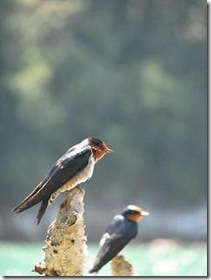

Natural environment that we still possess

by Eugene Pek, 30 October 2008, Pandan Terrace

The work of Mother Nature is beyond comprehension. The use and non-use values of these nature's masterpieces make up the total economic value.

Self-taken photographs, Oct 2008

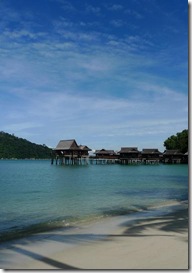

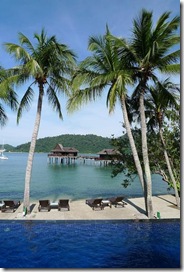

Good blend of nature & development

by Eugene Pek, 29 October 2008, Pandan Terrace

Balanced development and a good blend between economic motives and environmental preservation.

Some self-taken photographs at Pangkor Laut Resort.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Will you allow beautiful beaches to erode by rising sea level?

Forests' worth

by Eugene Pek, 28 October 2008, UTAR Sg Long

by Eugene Pek, 28 October 2008, UTAR Sg LongMangrove forests: What about them?

by Eugene Pek, 28 October 2008, UTAR Sg Long

by Eugene Pek, 28 October 2008, UTAR Sg LongTuesday, October 28, 2008

How much are hornbills worth?

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

New Dimension: Agricultural Multifunctionality (AMF)

1. Economic function

This role relates to the direct economic benefits accrued to farmers from crop planting activities. Jamal found that average farm projects in his sampling site have had slight positive effects on agricultural income and consequently, on total income generation in 2004 and 2005 relative to the previous years.

2. Social function

This function is discussed in three different contexts, i.e.:

2.1 Altruism value (AV)

This is the benefit derived from the traditional sharing of wealth made possible through paddy plantation especially in the muslim community. In the same work, Jamal estimated the AV to be USD10.3 million.

2.2 Employment opportunities

Even though agriculture contributes only 16 percent of the total employment in the country, paddy plantation specifically, does play its role in the provision of employment. On average each hired labourer received payment of some USD 7.90 per day and aggregate returns per annum or the value of employment opportunity benefits is highly substantial at USD 31 million.

2.3 Sheltering function (SF)

This function is critically important in times of economic recession as a taker of excess or unemployed workforce from urban areas. In

3. Environmental function

Alike the social function, this function is discussed in three different contexts, i.e.:

3.1 Flood mitigation function

Paddy fields are good rain water storage ‘tanks’ during the monsoon seasons, preventing floods in the nearby cities. Jamal asserted that this intangible value is one the most valuable contribution of paddy fields to the ecosystem. The estimated value of the flood mitigation function is approximately USD 0.034 million.

3.2 Heat mitigation function

Literatures show that paddy fields play an important role in heat mitigation. Empirical investigation found that USD 53,350 can be saved from the cost of cooling systems by the reliance of heat mitigation on the ecological function of paddy fields.

3.3 Air pollution reduction function

Air pollution is one of the environmental problems in the country, much so with the presence of haze sent by the forest fires in the neighboring country,

4. Food security

This function of the AMF is to ensure adequate level of rice production in the country at all times for the ever increasing population. Report has found that with a simulation of 20 percent decline in rice production due to the liberalization of free trade, urban Malaysians are willing to pay (WTP) a price premium of 33 percent i.e. around USD 1 per month. As an aggregate the estimated value of this function is USD 9.2 million annually.

5. Cultural function

This cultural function is an addition to Jamal’s selected functions. Like Japan and many other countries, Malaysia values agricultural activities and rural landscape dearly not only for commercial reasons like food exports and tourism but the cultural values they offer that help create strong communal bonds. Agricultural is a way of life to the Japanese as evident in the work of Goda, Kada and Yabe (2006) which talks about these amenities as the pride and ‘brand name’ of their hometowns. Autumn festivals as thanksgiving of good harvest and ‘Obon’ reunion time are still being practiced widely in

Acknowledging the increasing importance of these agriculture multifunctions, there are efforts in promoting these new dimensions in the country. Activities aim at inculcating more awareness and appreciation of the public are based on the objectives of making more multimedia awareness of AMF and a good example is the television advertisement of Sime Darby (the biggest oil palm producing company in the world), showing the importance of having sustainable palm oil production towards a more balanced growth.

These are important initiatives but may not be sufficient to drive more intervention from the government sector into recognizing AMF as a crucial element in sustainable development. The following sections discusses call for sustainable development (particularly in palm oil production) due to conventional reasons and offer some extended profound thoughts on AMF which may be worth deliberating.

Global Social Equity? Should the rich pays for rainforests?

The issue of sustainable development is a question of efficiency in ecological management.

There are several world renowned national parks in the country like the National Park, more known as Taman Negara,

At this juncture, the discussion aims to highlight the need for a biodiversity market to create a world trust fund that would aid the high conservation costs of national parks in the country. The fund can channel monetary aids to the state government to ensure ling-term sustainability of those parks which are dearly valued by the world. Chichilnisky, who proposed and wrote the global trading of carbon emissions with preferential treatment for poor countries which became part of the Kyoto Protocol adopted by 166 nations in December 1997, noted in her environmental sustainability conference lecture at Monash University Malaysia in December 2007 that she is working on a similar model for biodiversity market. With this market in place in the near future it will be excellent to see preferential treatment being given to the developing countries like

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Will environmental values change David Ricardo's comparative advantage?

Malaysian agriculture: Its sustainability issue

Should rich countries pay for rainforests?

What can climate deal do to help credit crisis?

2007 Nobel Peace Prize Winner: Al-Gore on Climate Change

2008 Economic Nobel Prize Winner: Paul Krugman

Monday, October 13, 2008

Valuation on peatlands is obviously possible.